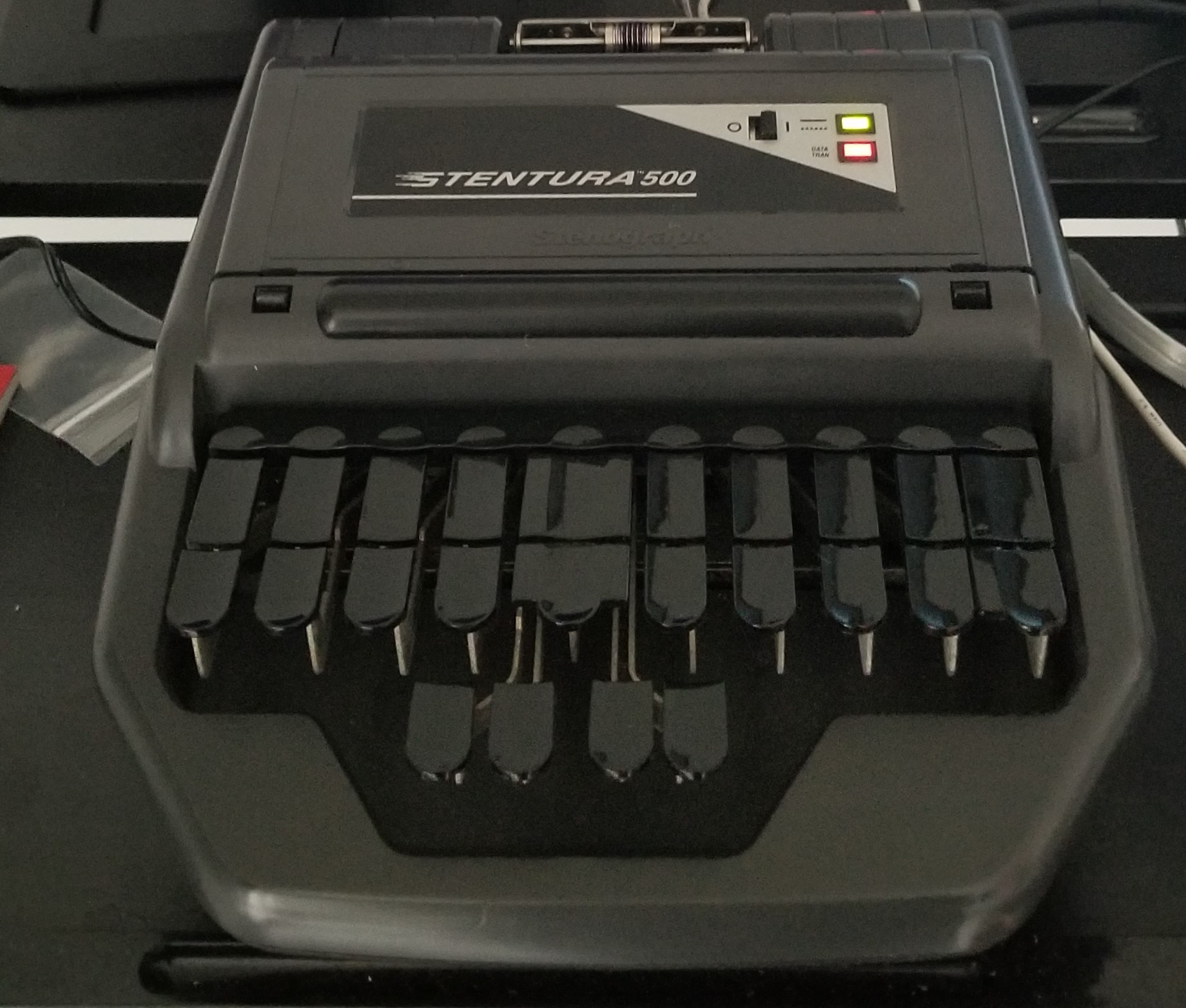

So, a few months ago, I found a book called The Art of Chording, which was about writing things out with an old device called a stenotype. You can see mine here.

It’s a tool that was mainly used by court reporters, which would allow them to transcribe human speech using a system of shorthand. I ended up being quite fascinated by it. Should you master the system, you could write at speeds of up to 300 words per minute! The idea of it was intoxicating. I could write at about 100 as it was already, but to go that fast seemed like it would be really cool. Not only that, but the fact that you could do this while hitting less keys and writing slower than a standard keyboard overall seemed like an ergonomic dream: you did not have to move your hands nearly as much to achieve the same level of efficiency! As someone who is fully dependant on my hands for livelihood, I thought that this would be a good skill to get my hands on it.

It’s certainly a weird little thing. The layout you do use is nothing like a layout that you’re used to using: you don’t have a full alphabet, and some of the keys appear twice. Yet, these are all the keys that you need to type at a level that most people could not hope to type at!

At this point, I’ve been practicing this skill for a few months on and off. I still think that it’s very cool, but I’m not the best at it. It’s definitely a skill you have to diligently learn over a few years of time. Superficially, it’s very similar to typing, but in actuality, it’s not much like typing at all. In typing, you have to learn the keys, and with any combination of keys, you can type any word your layout can let you type. On a steno keyboard, every word you write is done on a phonetic basis, and the way that those phonetics behave is dependant on the system that you learn to write with and augment. Many common words and word combinations are compressed into symbols known as briefs, which simply have to be memorized. In this way, it is much harder than learning a new keyboard layout. You have to in essence learn a whole new phonetic system in addition to learning a new keyboard layout, so often you end up struggling to write a new word you haven’t encountered before in a way that you just don’t in a standard keyboard layout.

But once you do learn the word, or the rules to make words that sound a certain way, you get into a very magical flow. It’s a feeling to really behold, when you are typing away at your thoughts on something, and the words come out just as fast as you can type them. I’ve never felt quite as connected to what I’m writing as when I’m writing well in steno.

I ended up liking it enough, that I bought a real steno machine so I could use it as my main keyboard as I work at my job, which has accelerated my ability to use the layout a lot. This whole article is written using a steno machine, in fact!

While the design is in many ways less ergonomic than I like, I think it’s a joy to write on. A lever machine is so light to type on, and the key’s shapes make some chords easier to write, since you can strike two keys by pressing straight between them with your nail.

How to do it

Alas, to do any of this with any level of efficiency, you have to at least have a keyboard that has NKRO. I, at the time that I discovered this hobby, had a Das Keyboard model 3, which could do NKRO, but only on a PS/2 interface, which my PC did not have, being made in the last ten years. So I ended up upgrading my keyboard to a ZSA moon lander.

You can try to approach stenography with only a standard 6 key rollover, but if you do, you have to arpeggiate the keys, which will slow you down considerably, and teach you bad habits. I chose not to do this. Also, the layout of most keyboards is staggered, which is not a nice layout for steno. A real steno machine is ortholinear, so that near every finger will govern two keys. This is important, because a steno layout does not have all the letters that you need to type all words. Instead, many sounds are written as shapes made out of multiple keys, often in a column, so you can press two keys with one finger. You often end up pressing more keys to make simple words, but because you are mashing them at the same time, you end up writing those words in a much faster manner than you would with a regular keyboard.

Once you have good hardware, you can go and start using and practicing the layout.

To practice steno is to be bad at it. It takes a lot of effort to be good at it. To type at the speed you normally do, it might take a few good months of struggle, because the system is going to be quite alien to your mind, and how you have been used to typing. In a way, though, it does remind me of my days of learning qwerty in school, and being awful at it, until I did reach that critical level of understanding and began breaking my speeds at hunting and pecking which is very reassuring.

You will need plover, which is an open source steno engine. It will take what you write in your keyboard layout, and write the actual word you mean to type.

In steno, you aren’t directly writing words. You’re writing a form of shorthand. For instance, if I write “For instance”, I’m actually typing “TP-R EUPB STA*PBS” which is then translated to the set of words that you’re reading right now. To be able to write well is to have a dictionary defined that fits the way that your brain can understand words, or strings words together. The way that you write those words is called a theory and there are many ideas on how you ought to write words using this sort of keyboard.

A lot of theories are commercial products, but there are a few that are free. In the end, you will end up having to extend your dictionary to suit the words you use in your daily life. In general, there is a trade off between a theory that is composed of easy to discover rules, and a theory that relies more on memorization; the latter are going to be faster, but require you to learn more to be proficient. It’s not worth trying to change from the default plover theory until you get a little bit of practice in and see if you even like to use steno in the first place. I personally use Lapwing as a base, which cleans up a lot of the inconsistent aspects of the default plover dictionary.

Symbols and modifiers

There are a few ways to do this, but I like to use Emily’s symbols and Emily’s modifiers. These add a bunch of chords so you can perform shortcuts and make symbols, many of which do not appear on a regular keyboard. You can also define your own in your dictionary. If you’re using a regular keyboard to do this, you can just switch between modes to accomplish different tasks, but I do still like to stay in steno mode as much as possible.

Problems

There are quite a few challenges with using steno as a daily driver.

Your ability to write is tied to Plover. That means that you have to revert to standard qwerty if you want to, say, log into your machine, since plover won’t be there on a login screen.

Since the system works based on a dictionary, you have to have the words you write defined in that dictionary, so you will have to build up a vocabulary on your own for any terms that you use that wouldn’t be in a common dictionary.

Editing a text is a challenge for me still. You can go forward and write quite quickly and well, but if you want to edit your thoughts it can be a lot harder to edit a word after the fact with steno. But this is a thing that I struggle with in general as I like to edit what I write a lot. Steno is written in blocks, and it’s written on key up rather than on key down, so you can’t navigate by just holding down your movement keys or deletion keys, as I have made a habit of doing. You really have to be able to move and edit things in terms of words, which is taking me a lot of time to really get used to, and I’m not quite sure if all software really supports this. A thing that I have found very useful is getting used to the idea of retroactively making a word lower case, as in steno, you will have the sentence advance automatically, and sometimes when you edit, you will have been put into a capitalization mode which will need to be undone.

There’s also another aspect to editing that makes it a little harder, and that is the asterisk key. In steno, it’s the way that you perform a backspace, or a delete. But it works by deleting or undoing the last stroke that you made, so if you jump around in your text, the undo history will not match what you’re writing. That means that you’ll end up half deleting words if you’re not careful in remembering when youum around. Once you get it, it’s not too bad, though, and it does work great in most cases.

Is it worth it?

Even with these drawbacks, I still like to write with this system a lot better than I do with a regular keyboard whenever I can get away with it. I’m not a whole lot faster than I was when I used a regular keyboard in many cases.