Writing in unusual ways is a hobby of mine. I’ve worked with machine shorthand for a while. But machine shorthand isn’t exactly a nice thing to input into a machine, unless you have a specialized keyboard that can handle chording. And as a way of representing text on a sheet of paper, it’s not at all suited. Who would want to write TP-LT for period on a memo pad?

Before machines ruled the courtroom, the court stenographer used a memopad and a system of vague squiggles that allowed one to quickly write words. In the UK, they used Pitman. In the US, they used Gregg. Pitman emphasizes the width of the stroke, so you would need a nib that can stretch to make it work. Gregg, on the other hand, works out on a series of lines and curves of uniform width, making it work just fine with a regular ballpoint pen. The fastest court stenographers used Gregg, and in particular, Gregg Anniversary edition.

It used to be that shorthand was a class. I’m too young to have learned Gregg in school. If I did, I feel like it would have been a massive boon in note taking. Instead, I wrote sloppy chicken scratch to try and meet the speed of the lecturer, while copying down powerpoints that didn’t have enough context to be particularly useful when I tried to review them later. I’m only lucky that I was able to remember the lectures reasonably well enough to complete the homework.

The principles of Gregg are pretty simple. Gregg is meant to transcribe speech, not write text. As such, it needs to be fast. Three principles make Gregg lightning fast:

- Words are to be spelled phonetically. There’s no need to worry about working through thourough thoughts about how to spell one thing or another. Homophones like “to”, “two”, “too” and “there”, “their”, “they’re” are all written the same, because they are spoken the same. Just write exactly what’s said.

- If a word is common enough, don’t write the whole thing. Write a shortened substitute. No need to write “the” every time. You can instead just write “th”. Or “n” instead of “in”.

- Every sound in English can be written with a single, easy stroke of the pen. There’s no doubling up letters or extending a single sound into two or more strokes like you might have to do with “Q” or “E”.

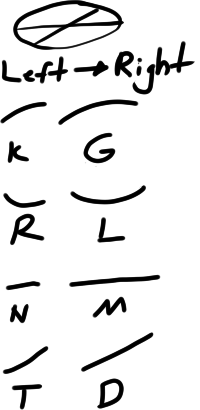

Consonants are cut out of a pair of circles crossed out with lines:

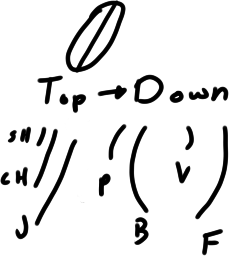

Vowels, on the other hand, are variations of pieces of a circle:

You combine these two principles to write any word in a single stroke, by looping vowels between consonants. If you’re feeling clever, you can omit the vowels where they are unnecessary to understand the word. So for instance, you might write “Fingr” instead of “Finger”. You can also combine common words that tend to bleed together, so instead of writing “in the”, you might prefer to quickly write “nth”. There are three other sounds like “s”, “z”, “h” that I omitted from those very simple diagrams, but they are very simple exceptions. “s” and “z” are short hooks that hang off of either side of a stroke. “h” is represented as a dot above a vowel.

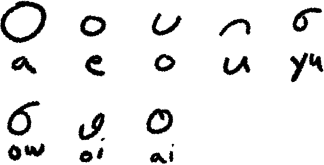

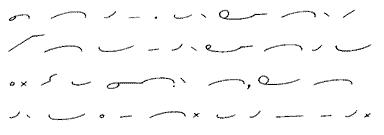

How does it look? Well, if you were in a meeting, and a colleague was writing in Gregg in their notebook, and you didn’t know what it was, well, you’d probably think he was absolutely bored out of his mind doodling while the boss was explaining to the team what the development roadmap was. It’s like some toss away nonsense a cartoon character would scribble in a notepad while trying to take notes on the phone. When I looked at the examples from the Gregg Anniversary book, it felt like I was reading an elaborate practical joke insisting that this was some sort of discernible writing system:

But it is totally readable, and the only downside is that our modern lives and way of writing are so totally divorced from the world that the Gregg Anniversary was written in that you’ll sit there wondering whether or not “The hat lay there an hour. Her gay air will not go well here.” is actually a real coherent set of sentences or some sort of strange nonsense that you confabulated as a complete guess because you have approximately 10 minutes of knowledge on shorthand and virtually no knowledge of how people in 1920s America actually talked on a daily basis.

On that basis I would ignore all of the exercises in that book. Print out that first page that has the alphabet on it. Go through the first parts of all the chapters that teach you the strokes and how to stitch them together, and do drills to get it through your head how to make the loops efficiently and blend consonants together. Then, just write things in Gregg on your own terms however you think it makes sense. Machine stenography usually follows a very similar philosophy: you want to build your own vocabulary of briefs that let you efficiently write the common sentences that you yourself want to write, rather than sticking rigidly to one sort of theory which may or may not perfectly mesh with you.

It’s not a very space efficient way to write. In that way it feels like a writing system that’s practically the philosophical opposite of classical Chinese. You’ll be going up and down and around to write words, with some sounds necessitating a series of long strokes in a particular direction. For example, a word like “barf” can span a tall vertical space and practically no horizontal space, while something like “gleam” can take a very wide horizontal space while taking no vertical space. But once you get the hang of it, trying to write with an alphabet feels like a total slog as you painstakingly have to write character after character and your mind races far beyond the limits of your pen. I was hashing out a blogpost idea I had intended to be after this one using the standard latin alphabet, slurring the letters together in a demi-cursive, but it felt like typing into a 300 baud terminal: the words just lag so far behind the trail of thought.

Despite that singular disadvantage, I find it very useful. I’m still not too fast at using it, but I tried to deploy it at a small meetup that I joined at the spur of a moment. I wrote a handful of notes with my very meager knowledge of Gregg, and managed to capture all but two ords in a series of 6 pages. My phone has a stylus pen, and allows me to quickly jot notes in gregg. Without that I probably wouldn’t really have tried it at all, unless I brought my steno pad and pen.

You may ask yourself: Why learn such a system in a world where AI can transcribe a meeting into a perfectly readible transcription? I would say to that, that while you can indeed get a very useful transcription from some sort of external service, there is something about writing things in your own hand that is extremely beneficial to retaining the information that you’re transcribing. The hand has a very direct connection with the brain, and I find that simply having to process that information in a slightly different way while I’m listening to a speaker gives me a better ability to remember and act on what is being talked about. Even when people invented the dictaphone and began simply recording their conversations, there were people that still wrote in shorthand.

Another pipe dream project I have, had I more time, is to use models of the ellipse that Gregg is based off of, to make something that might recognize Gregg as an input method you might use on a phone, or a computer. I at first tried a machine learning approach but I found that the daunting task of compiling a ton of gregg literature and then slicing it into pieces along word and character lines rendered it far too much work for a singular person to even try. And even if you did, the ambiguities that exist in Gregg would make it a challenge to appropriately interpret, and even furthermore, if you wanted to be even half as useful as Plover, you’d need to be able to build up a personal dictionary, and I could not imagine the process of doing so for an average person with some sort of baked model. I think there is some way to do it using a more classical approach, but I am too deep in building other things to worry about it at this stage in the game.

I encourage you to try and write a little shorthand yourself. See if it steps up your notetaking game and helps you retain information that you otherwise wouldn’t have!

Write to me on the fediverse at @tmk@social.lugal.io if you have feedback!