The Titanic was a tragedy that required a crazy set of circumstances.

People love to focus on the lifeboats, and the fact that, even if all of them were fully occupied, there weren’t enough to save any more than half the passengers on ths ship, but in the actual disaster, the crew couldn’t even properly launch all the lifeboats as it was. In fact, they didn’t even properly fill many of the lifeboats before they were launched. There was simply no chance that they were going to lower all of the davits before the ship went under. The only way to avoid the tragedy was not to lower all of the passengers into lifeboats, but to heed warnings and be proactive in avoiding the icebergs in the first place, as many ships had warned the Titanic previous to the disaster.

In reality, there was only a very narrow window where the tragedy could have unfolded as it did. If Frederick Fleet were to report the iceberg just seconds earlier (by observing directly from the bow as the lookouts of the Carpathia did as they raced through the minefield that was the North Atlantic trying to get to the Titanic, or perhaps, by simply having a telescope), the skipper could have very slickly moved perfectly around the iceberg as they were hoping to do. The ship could have made their maiden voyage unscathed with a large, lumbering dodge.

Now, I have piloted a small pontoon boat before, and compared to a bike or a car, maneuvering it is incredibly unweildy. Getting it to land exactly into a dock is an adventure unto itself. It’s mind boggling to me to imagine how difficult it would be to promptly turn a 52k ton ship with such massive inertia to avoid a calamity as the Titanic faced!

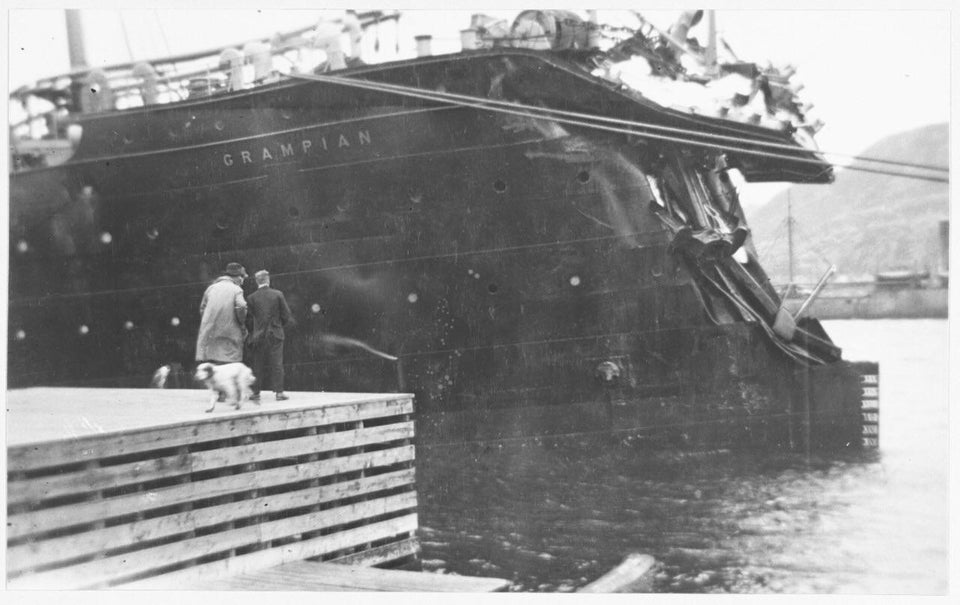

However, if Mr. Fleet were able to report seconds later, they would have hit the iceberg straight ahead. That sounds like it could have resulted in an even worse fate, but by hitting it straight ahead, only the first two compartments would have flooded instead of the near-miss scraping six compartments and overhwelming the safety mechanisms built into the ship. It would have resulted in many deaths, particularly in the crew who would have been sleeping in the forecastle, but most of the passengers would have survived, albeit with an embarassed high command driving a ship with an absolutely gnarly front end. We know this; there have been at least a few all-metal ships that accidentally ran into an iceberg, completely destroying their bow but still easily capable of making their full voyage. For example:

I won’t say that the bridge truly made the wrong call to try as they did to get the ship off the trajectory of the iceberg. With what information they had going into it. Imagine her reputation for unsinkability if she sailed into the harbor like that.

When it comes to disasters, it’s very easy to focus on the lifeboats. The goal of the lifeboats in a mid-ocean disaster is to efficiently ferry people to a ship that can take them before the ship goes down. You want to have lifeboats, but you don’t want to use the lifeboats if you can help it. And if there’s no shore to row to, no ship swiftly coming to the rescue before wind and current scatter everyone, you have only turned a swift death into a slow one. Even today, with all the benefits that technology has afforded us, it is a major challenge to find something so tiny in such a large area. The lifeboat is just one critical piece of a real plan of action. What could have been better?

- The tools and protocols for dealing with a clear night could have been better. The watch could have had telescopes. Some extra spotters could have been placed around the bow.

- Warnings from other ships in the area could have been heeded. Someone could have been more cautious and slowed down, even if it weren’t standard operating procedure.

- Telegraph operators were doing overtime transmitting a backlog of upper class telegrams after dealing with endless technical difficulties and ended up being curt with other operators in the area who were trying to get warnings through.

How many times could have you avoided a problem, if you invested into the proper observability to avoid it? The proper testing to avoid it? The proper and careful rollout of the idea to see a change in action before any resulting disaster becomes worse? How many in leadership ever expressed that they “can’t imagine any condition that would cause a [modern] ship to founder” (as Captain Smith did)?

Behind every great disaster, there is a problem of process. Someone ignored something, because they wanted to get it out faster. Someone couldn’t do something, because they didn’t have the right tools in their toolbox to do it, or they couldn’t stand in the right place. One mistake in a system can often be accounted for somewhat easily. But two becomes harder, and three even harder still. When enough people can’t or won’t follow a safe method of working, you simply tempt fate.